| 阅读上一个主题 :: 阅读下一个主题 |

| 作者 |

留言 |

hgy818

注册时间: 2007-09-13

帖子: 1298

|

发表于: 星期日 十一月 11, 2007 9:18 pm 发表主题: 罗伯特·韦尔:被敌人反对是好事——评乔·哈利迪、张戎《毛泽东 发表于: 星期日 十一月 11, 2007 9:18 pm 发表主题: 罗伯特·韦尔:被敌人反对是好事——评乔·哈利迪、张戎《毛泽东 |

|

|

作者: 东门之阪 发布日期: 2007-11-10 查看数: 8 出自: http://www.wengewang.org

来源:工农之声

白云黄鹤按:向大家推荐一篇好文章——《被敌人反对是好事》。

作者是一名美国人,名叫罗伯特·韦尔,美国加州大学教授。这篇文章不仅是为毛泽东辩护,更重要的是他揭示了全世界反动派,包括中国的反动派,看到毛泽东对他们生存的威胁,他们发出了歇斯底里的呼喊。

为什么中国的知识精英和主流学者不能为自己的领袖受污辱而写出这样的文章呢?相反,从批“两个凡是”、“破除迷信”、“实践是检验真理的标准讨论”,一直到大量“伤痕文学”的出笼,都是妖魔化毛泽东的。有那么几位大人物,还到处宣扬“毛泽东有罪”。十七大前夕,由几位党内高级人士支持的《炎黄春秋》杂志派了一个“代表团”到香港去游说。前中国人民大学副校长谢韬,代表“这样一批人”演说:“要重新评价毛泽东,重新清理毛泽东几十年来的罪行”。他们是和全世界出现的由帝国主义反动派所掀起的反毛泽东潮流相呼应的。

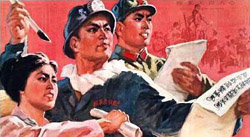

最近,有个叫张戎的女人,自称是文革时期的红卫兵,写了一本书——《毛泽东,鲜为人知的故事》。帝国主义者开动了所有的宣传机器来热捧。这本书把毛泽东变成了一个杀人如麻,生活放荡的恶魔。

中国共产党的舆论机关,对这本书一直缄口不言,而是由一个外国人来进行揭露和批判,岂非咄咄怪事。

这篇文章对我们最大的启发,正如它的标题所示:《被敌人反对是好事》。为什么毛泽东已去世三十多年,帝国主义反动派,中国的反动分子还这样痛恨他呢?因为毛泽东的“幽灵”,仍指挥被压迫、被奴役的人们在进行战斗。

从委内瑞拉到巴勒斯坦,从世界屋脊的尼泊尔到海滨椰林的菲律宾,解放战士都在读毛泽东的书,毛泽东招唤他们去战斗。

在中国,被赶出工厂和家园的工人们,举起“造反有理”的旗帜;失去土地的农民,佩带着“赤卫队”的袖章,维护着毛泽东曾给予他们主人公的权利。

《被敌人反对是好事》这篇文章,让我们看清了世界大势、中国大势。

走,跟着毛泽东走!

·白云黄鹤·

被敌人反对是好事——评《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》

美国南加州大学社会学系教授 罗伯特·韦尔(1)

李新华、曲广为译 张运成校(2)

“被敌人反对是好事而不是坏事”,我一直认为这是毛泽东语录中最有价值的一句话。它不仅改变了我的斗争观,而且也许比毛泽东的任何其他语录都更为简练地浓缩了毛泽东思想和策略的深刻辩证性。正是此种辩证性,使毛泽东能够利用敌人之间的矛盾去“排除万难”,一次又一次转败为胜。毛泽东指的,并不是敌人的反对所造成的损失和苦难,他认为那是为革命必须作出的“牺牲”,并在诗中写道“为有牺牲多壮志”。(3)被敌人反对是“好事”而不是“坏事”的原因在于,敌人的反对意味著革命力量进行的斗争是成功的,它把敌人打疼了,对其统治构成了挑战。

要不然,为什么那些反革命势力甚至会为反对我们而烦心?那是因为敌人越少克制自己,暴露出的弱点就越多,就会使他们看不清现实。毛泽东说过,“如若敌人起劲地反对我们,把我们说得一塌糊涂,一无是处,那就更好了,那就证明我们不但同敌人划清界线了,而且证明我们的工作是很有成绩的了”。(4)因此,革命者受到的反对愈是猛烈,说明他们取得的成绩越大。而那些反革命的人仅仅是出于仇恨而作出的轻率结论,将会使他们犯下严重错误,并使其在人民当中名誉扫地。

最近出版的张戎和乔·哈利迪合著《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》,不仅对毛泽东个人的领导地位,而且对他领导的那场革命的全部历史,对中国乃至全世界——社会主义事业是其中一个重要构成——为实现社会主义而进行的斗争,进行了无情而又令人恶心的攻击。该书在美国出版(此前在英国和亚洲已经能够买到),其写作手法和调门哪怕是一位粗略读过的读者都能迅速领会。不过,英国广播公司(BBC)

“新书速递”栏目摘播的内容,已使该作品的性质昭然若揭。通常,该栏目更多地是摘播小说。显而易见,毛泽东生活当中的所有行动和事件都被最大可能地进行了负面解释。

2005年10月20日美国全国公共广播电台对作者进行的一次采访,以及五天后英国广播公司的另一次采访,都验证了这个事实。该书的美国版本面市之前,有关评论也已经清楚地说明了其品性。正如那些评论家普遍阐明的那样,这本书的出发点,就是要从最细微处着手,毁掉毛泽东作为领导者乃至作为人的形象,否认过去中国革命的社会主义性质。在这本书中,毛泽东这位中国人民民族解放斗争和社会主义革命的主要领路人,被描写成一个胆小鬼,藐视农民,他从革命造成的死亡中获得乐趣,只会通过恐吓和玩弄权术进行统治,而且私生活放荡。这本书已引起西方主流评论界的关注,至少某些被称为“新中国通”的评论家在认可书中披露的内容时的热情,要比先前对李志绥的《毛泽东私人医生回忆录》时高得多。英国广播公司也迫不及待地认可了这本新书,虽然把其称为经过精心研究的非小说类作品,但在摘播《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》时,用的却是一种富有“戏剧性”的冷嘲热讽的语调。

已发表的评论,都对该书的权威性表现出一种相似的深信不疑。其中有一位评论家称该书是“一部具有无可辩驳的权威性的著作……总体来说,毛泽东自始至终无论在小节还是大节上都并非那么光彩;他是杀人犯,是虐待狂,是没有天分的演说家,是好色之徒,是文化破坏者,是贩卖鸦片的奸商,是惯于说谎的人”。(5)该书声称毛泽东要为七千万中国人的死亡负责,这大大超出了其他激烈争议的说法中提出的最大数字。“张戎说:‘毛泽东的邪恶和给人类造成的损害,犹如希特勒或是斯大林’”。(6)即使是如此诋毁,对某些评论家来说仍嫌不够。在把毛泽东与前俄国领导人进行了比较之后,西蒙·塞巴格·蒙蒂菲奥里声称,“毛泽东是他们当中最大的恶魔——中国的红色帝王”。(7)菲利普·亨舍自一开始就加入了那些热情过头的评论家的合唱当中,用与他们类似的语言谴责书中提到的“所有残暴的事情”。该书在美国出版之后,最初的评论完全是在鹦鹉学舌。《纽约时报》刊发的一篇书评,其标题为《中国恶魔,首屈一指》,作者角谷美智子(Michiko

Kakutani)认为该书“以令人感慨不已的事例表明,毛泽东是所有时代中最恐怖的暴君”。(8)两天后,尼古拉斯·克里斯托夫在《纽约时报书评》上发表的一篇书评,仍在重复上述论调,语言毫无新意,完全是在自说白话。尽管对该书的学术性以及资料的来源和准确性表示怀疑,并表示“我对该书的判断持保留态度,因为我自己的感觉是,毛泽东尽管残暴,但也给中国带来了有益的变革”,克里斯托夫仍宣称该书是一部“极好的传记”,是一部“富有权威性”的著作。(9)

上述评论中大多数流露出的不只是对毛泽东这位中国社会主义革命的领导者的敌意,他们或有意或无意地在胁迫任何对毛泽东的生活和成就持肯定态度,或者尽管持否定态度但要比张戎和哈利迪的全面否定稍显温和的人。因此,弄清楚《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》是在何种气候下出炉的,以及那些急不可待地认可该书的人的背景以及为谁效力就显得尤为重要了。显而易见,该书恰如其分地符合毛泽东本人在其文章中已经预言过的情况——“被敌人反对是好事而不是坏事”,“如若敌人起劲地反对我们,把我们说得一塌糊涂,一无是处,那就更好了,那就证明我们不但同敌人划清界线了,而且证明我们的工作是很有成绩的了”。正是该书完全片面的写作手法,使大部分评论家急不可待地去认可它,并对任何关于毛泽东地位的更加持平的分析视而不见。与其他许多人一样,我对这棵大“毒草”——这是澳大利亚塔斯马尼亚大学教授高默波对《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》一书的评语——的出版感到愤怒和惊愕。这部书以及许多赞美它的评论,已经在互联网和其他地方遭到中国和西方读者的挑战和鄙视。当最初的愤怒和惊愕过去之后,我想到的是这样的问题:为什么会有这样一本书,为什么要在现在出版这样一本书?在毛泽东去世近30年之后的今天,当前的中国领导人已经改变了他领导下的社会主义革命的方向,回到“资本主义道路”上——毛泽东早巳预见到这一点,并试图阻止此类情况的发生。如果说“被敌人反对是好事而不是坏事”,那么在今天,毛泽东身上还有什么东西会对敌人具有威胁?为什么中国社会主义革命的敌人,例如张戎、哈利迪以及他们的出版商乔纳森·凯普和阿尔弗雷德·克诺夫,感到有必要把毛泽东的遗产贬得一无是处,而且彻底性要比过去有过之而无不及?为什么中国之外的许多评论家感到有必要去热切地认可他们的书?毛泽东身上到底有什么东西与当今中国社会和世界上的矛盾和斗争息息相关,从而招来如此攻击?

在此,人们不能完全不理会出版该书的个人和经济因素。对张戎而言,毛泽东尤其是他领导的文化大革命,仍旧是让她痛苦不堪的根源和产生报复心理的动机。张戎曾为自己的家族写过一本名为《鸿:三代中国女人的故事》的传记,在书中,她特别把描写的重点放在其父母、后来是她本人在最初毫不怀疑、满怀热情地信奉毛泽东之后产生的幻灭感和被背叛感上。这段个人历史,是隐藏在新书深处的写作动机。有评论认为:

对毛泽东的毫不宽恕的敌意,以及罗列证据把毛泽东抹黑成为一个极端自私的人和虐待狂的决心,促成了《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》的出版。对张戎而言尤其如此。在文化大革命开始之初,十几岁的她还是一个满腔热情的红卫兵,但当目睹从事学术研究的父母遭到残酷迫害之后(其父被迫害致死) ,她改变了自己的态度。(10)

这种情况已是屡见不鲜。正如那些熟悉此类作品传统的人所知道的那样,它们往往出自那些最狂热的前革命信徒之手,而在他们完成“转变”之后,随之就会对过去进行最恶毒的攻击。在评论《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》时,人们不能无视个人恩怨方面的因素。此外,《鸿:三代中国女人的故事》已售出大约一千万册,无疑给张戎带来了丰厚的金钱回报。今天,“借助于从她的那本全球畅销书中获得的收益,(张戎)在伦敦诺丁山的高档社区中过著非常舒适的生活”。(11)据此推测,无论是作者还是出版商,都希望纽约能够借新书复制前一次的成功。

不过,显而易见的是,该书并非只是想获得个人满足——无论是情感还是金钱方面的——那么简单。像《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》这类书,显然具有政治目的。对于那些对中国的共产主义革命——无论其采取何种形式——充满敌意的人来说,今天的中国领导人虽然已在很大程度上疏离了毛泽东并完全改变了他的政策,但这并不足以让他们感到满足。今天的中国领导人仍自称“共产主义者”,而高高悬挂在天安门城楼上的,仍旧是毛泽东的画像——那里可是全中国最具象征意义的中心地带。甚至时至今日,中国领导人仍要在很大程度上借助毛泽东的遗产来维系他们日益减弱的合法性。正如乔纳森·米尔斯基对当今中国领导人的质问那样,“为什么在今天仍要维护毛主席?因为如果没有毛泽东,中国共产党的脚下就会裂开一个黑洞……如果没有毛泽东,他的继承人——无论他们是什么样的人——就会在意识形态上摇摆不定、陷入虚无。这位前伦敦《泰晤士报》东亚版编辑,《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》的又一位热情评论家继续写道,“因此,对当前的(中国)领导人而言,毁掉毛主席的形象将是灾难性的。毕竟,这些领导人仍在继续强调‘中国共产党会犯错误,但只有党才能够纠正错误。’……可如果党本身就是一个错误,而毛泽东是一个更大的错误,那又将如何呢?中国领导人决心阻止此类思想在中国广大民众中的散播。”毋庸置疑, 这是必须写作《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》一书的主要原因。对像张戎和哈利迪这样的反共分子和许多评论家而言,毛泽东的名字必须被抹掉,甚至连当今中国领导人与毛泽东在形式上的联系也必须被掐断。唯有如此,中国才会再次“摆脱”毛泽东领导的革命以及他所追求目标的残留影响。

可是他们为什么如此关注毛泽东?毛泽东又怎么会时至今日仍能把敌人打得如此“疼”, 以至于他们感到有必要采取如此史无前例的行动,满怀敌意和愤恨地把他领导的那场革命的历史歪曲得面目全非?为什么他们连那场革命斗争的细枝末节都要否定?为什么他们要把毛泽东变成一个比世界上的其他任何领导人都恐怖的“恶魔” ?为什么毛泽东的地位仍是如此至关重要,他遭到反对是“好事”而不是“坏事”?最后,那些仍旧坚信中国社会主义革命目标的人,应当如何以毛泽东那样的辩证态度来应对此类攻击,从而在面对挫折和反复时,能够扭转乾坤?答案就在于,在一定程度上,张戎、哈利迪对毛泽东的攻击表明,甚至在今天他仍旧代表著中国人民的利益。中国正在崛起,全世界都在为如何适应这个新现实而苦苦思索。正如西方世界一贯的做法,在应当把中国实力的飞速发展视作机遇还是威胁问题上,美国和大英帝国的领导人,尤其是他们在学术界和大众传媒的吹鼓手如张戎、哈利迪感到左右为难。一方面,对于全球的资本家来说,中国这个发展中的巨大市场的诱惑不可抵挡。另一方面,他们不仅害怕中国在经济上强大起来,而且害怕伴随著经济上的强大,中国的政治、军事力量也会飞速增长。

这个问题成为当今美国主流媒体上的永恒话题,不只是右派媒体,而且包括自由派媒体和进步媒体。2005年7月17日的《圣何塞信使报》上的一个大字标题——“中国世纪正在形成”,就表明了这一点。大标题下文章的作者是奈特里德公司(KnightRidder)的提姆·约翰逊,文章开头写道, “如果说20世纪是美国的世纪,那么21世纪也许属于中国。入世不过五年,中国已经成为全球第三大贸易国,成为全球增长最快的经济体,成为东亚地区正在崛起的军事强国,成为影响力已经扩展至非洲、中东和拉美的全球事务的重要参与者。”随后,《纽约时报》也以“谁在害怕中国公司?”为题,表达了它对这个问题的关注,分析了为什么甚至连那些“自称支持自由贸易的人”,也开始担心中国对美国“国家安全”的威胁。(12)专栏作家罗伯特·萨缪尔森也对最近中国公司竞购美国尤尼科石油公司一事进行了分析。在美国的政治反对势力将会阻止此次竞购的事实已经再也清楚不过的时候,中国公司放弃了竞购计划。萨谬尔森说,“我们无法断定中国是威胁还是机遇,而在我们作出决定之前,有关两国关系的所有讨论似乎都会陷入混乱和刻薄。”(13)

2005年6月27日的《时代》杂志,也表达了同样模棱两可的态度。这期专刊的标题很长——“中国的新革命:重塑世界,步步为营” ;副标题则反映出既害怕中国的崛起,又把中国的崛起视为机遇的矛盾心理———“中国来了!中华人民共和国的崛起是否意味著美国的衰落?”,“中华人民共和国从未像今天这样热情地拥抱世界。我们该为此而庆幸还是该为此而忧虑?”

对于那些认为中国的崛起更多地是威胁而非机遇的人来说,足够糟糕的是,即使是一个资本主义中国的崛起也会对美国的全球霸权构成挑战。但如果中国人拒绝抛弃他们的历史,并再次走上社会主义革命的道路,那危险就会更大。因为如果那样,不仅美国帝国会面临威胁,就连全球资本主义的根基都会面临威胁。因此,中国必须与它的革命过去“彻底告别”,甚至连一丁点革命的残迹都不能留下,而中国的“新革命”必须是一种安全的“美国模式”,也即只能致力于构建“自由市场”和“做生意”而不能致力于实现社会主义和工人阶级的利益。但问题随之出现。这期《时代》专刊的封面人物,既不是在毛泽东去世后把“市场化改革”引入中国的邓小平,更不是当今中国的国家主席胡錦涛。《时代》选择毛泽东来代表中国,把他那幅以光芒四射的红太阳为背景的画像作为这期专刊的封面。在文化大革命的岁月里,这幅画像曾经广为流行,颇具象征意义。在某些人看来,自1949年10月1日站在天安门城楼上宣告“中国人民从此站起来了”以来,毛泽东就已成为中国现代化崛起的象征。因此,必须与他留下的遗产进行斗争,这关系到中国的崛起是机遇还是威胁,关系到中国是朋友还是敌人。在那些把毛泽东领导的革命视为当今世界的最大灾难和危险的人——例如张戎、哈利迪之流——看来,坚决毁掉毛泽东作为中国象征的地位至关重要。正在崛起的“新中国”,必须彻底消除毛泽东的榜样力量,转而去苍白地模仿西方,从而顺利地融入美国主导的世界帝国和资本主义的“全球化” 。在上述观点看来, 英美“自由世界”象征著乐土——在《鸿:三代中国女人的故事》的结尾,张戎最终逃到了那片乐土。在他们看来,只有把毛泽东彻底妖魔化,只有彻底否定而不仅仅是抹黑毛泽东领导中国人民进行的社会主义革命事业,中国才能最终摆脱时至今日仍如幽灵般在中国游荡的“毛泽东主义”的毒害,中国人民才能体验到西方式的“自由”。

在《鸿:三代中国女人的故事》出版后不久,张戎和哈利迪即著手写作《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》,并花费了十年时间来完成该书。但他们出版该书的时机,却是在中国的性质已不仅在国内引发争论,而且在全世界都引发争论的时刻。只有在这场斗争的背景下,才能正确地理解他们对毛泽东的攻击——那不过是一场更大规模斗争中的一小部分。这种斗争不只攸关中华民族命运。毛泽东是中华民族复兴的领导者和象征,为此,中国人民——无论其属于何种社会阶层——都在深深地崇敬他。不过,对于今天的矛盾而言,毛泽东作为中国社会主义革命事业领导者的地位更为重要。中国在崛起,但中国的农民和工人对“改革”时代资本主义剥削的反抗却日益强烈。对于中国工人阶级来说,他们当中许多老人的记忆里仍保留著社会主义是基本国策时的生活片断,毛泽东仍然象征著免遭剥削、失业,象征著社会保障,象征著没有严重的两极分化和“改革”造成的腐败。不过,这决不仅仅是一种怀旧之情,或者是一种认为在“过去的美好日子”里一切都好的朦胧感觉。对于当前中国工人和农民的斗争而言,——毛泽东仍然是一个重要的参考,他们频繁地翻阅著他的著作,希望从中获得鼓舞和指引。

当然,中国领导人对于这种联系不会没有觉察。随著中国广大工人阶级状况的恶化,甚至连中国的官方媒体也不得不去面对日益严重的两极分化问题和可能出现的革命幽灵。美联社发表评论说:

中国国家媒体……引用官方研究数据说,中国的贫富差距正在达到一个危险的水平,可能导致社会动荡。

中国官方的新华社报道,占人口五分之一的富裕阶层占有社会百分之五十的财富,而占人口五分之一的底层民众仅占百分之四点七。……

该报道说,“收入差距已经超出合理的限度,而且还有拉大的趋势。如果持续下去,不利于社会稳定。”

在当今中国,贫富差距随处可见,从蹒珊在上海市区垃圾箱之间回收塑料瓶的老年人,到上海郊区被挤压在豪华别墅之间的流浪者的陋室,不一而足。(14)

在报道中,新华社尽力暗示社会不满不仅仅是潜在的,已经极大地蔓延开来。对这家官方新闻机构来说,情况继续恶化下去会出现什么后果是显而易见的。因为它知道,对于社会主义革命的记忆从未在中国工人阶级的意识中远逝过。在美联社的报道中,有这样一段话:

在(他们)的话语中,会提到革命的毛泽东时代。那时,共产党对私有企业实行国有化,并剥夺了富裕农民的土地。这是中共发动的最为极端的运动之一。(15)

而今, 随著私有化再次受到官方的提倡,中国农民面对的是相互勾结剥夺他们土地的村干部和企业,其转而发动更为革命的斗争行动的潜在可能性再次浮出水面,这令北京领导入感到担忧。

世界上一些最大规模的工人阶级抗议活动实际上每天都在中国各地发生,不过这个事实在很大程度上被西方所忽视。这些抗议活动包括:发生在中国南部沿海地区外资出口企业的罢工, 发生在中部和东北部老工业基地的示威活动, 以及针对腐败官员和东部城市郊区和西部偏远地区环境灾难的抗议活动。《纽约时报》的一篇报道引用中国公安部的数字说,中国的“群体性事件、示威活动或者骚乱”从十年前的不过一万件,上升至2003年的5.8万件和2004年的7.4万件。该报道说:

面对不断蔓延的工业污染,以及当地腐败官员和势力日益强大的开发商相互勾结把他们从自己的土地上赶走,征用他们的土地,普通中国百姓似乎在说,他们已经受够了,不会再忍受下去。

每个星期都会有至少一两件群体性事件的消息传出:成千上万的村民与警察发生激烈对抗;在警察的围捕中,数百名抗议者遭到催泪瓦斯和棍棒的血腥镇压。根据中国官方自己的记录,远离公众的视野之外,每星期都会有数百件类似事件发生。(16)

这些示威活动已经蔓延到“市场化改革”的中心地带,例如上海,那里是中国商业资本的新中心。在这些斗争中,工人和农民往往不约而同地把毛泽东思想以及他制定的社会主义政策与今天他们日益恶化的社会地位进行对比。《纽约时报》的报道说:

在一次抗议活动中,中年居民引用他们年轻时在文化大革命中使用的造反口号——诸如“造反有理”之类,谴责为给高楼开发商让路而把他们从家中当场赶走,并要求合理补偿。(17)

不管他们在抗议中是否清楚地提及毛泽东的名字,但正是毛泽东为他们分析自己目前的状况并采取行动提供了一个历史参照物,并为那些反对当前资本主义的和腐败的“改革”政策的人提供了一个团结起来的基础。

为声援“郑州四君子”而发动的广泛示威活动,就是一个例证。“郑州四君子”是河南四位工人活动分子,他们散发传单谴责中国共产党目前的指导方针,并在纪念毛泽东逝世28周年的一次集会上宣读了这份传单。他们把毛泽东与当前肆虐的资本主义以及领导人的腐败进行了对比,呼吁他们回到毛泽东在世时的社会主义道路上。由于这一“罪行”,他们当中有两人被捕,并被判处三年有期徒刑。不过,这四位工人活动分子绝非是孤立无援。在不开庭审判他们时,中国各地的左派人士团结起来,网络上也出现有关该案的大量讨论,为四人的行动辩护。此外,一百多位中国人一鉴于面临的政治风险和通讯渠道的限制,这个数字已经非常大了——与同样人数的海外人士联名签署了一份请愿书,抗议关押四人。在声援具有战斗精神的四位左派工人问题上,出现了史无前例的国际大联合。此外,还有其他一些迹象表明,人们在拒绝遗忘毛泽东领导的革命斗争。在郑州工人聚居区的一个公园内,每天傍晚都有数百人,在周末甚至会达到千人左右,聚集在一起大唱老的革命歌曲,缅怀毛泽东时代。工人和农民往往会表达同样的看法:在中国走上毛泽东反对过的“资本主义道路”之前,生活与现在完全不同,要好得多。当然,上述看法并不普遍。有一些工人和农民从当前的改革中“获益”,他们当中甚至有一些人遵照邓小平的号召而“先富”起来。在当今中国,追求个人经济利益成为最重要的生活目标。尤其是工人阶级中的年轻人,他们对社会主义时代没有什么记忆,正日益被当前盛行的消费主义所吞噬。但是,正如“郑州四君子”案表明的那样,仍有足够多的工人和农民在斗争中还在从毛泽东那里寻求鼓舞。他们的斗争已经促使中共和中国当局,以及那些害怕中国重新实行毛泽东的社会主义政策和他领导的阶级斗争,尤其是回到文化大革命时代的人作出非常强烈的回应。而文化大革命,正是毛泽东为防止中国回到“资本主义道路”而发动的最后一场大运动。

社会矛盾在迅速增加,抗议活动的规模也在不断扩大,而且不只限于上面提到的工人阶级的斗争。到目前为止,这些示威或者暴乱大多数都是孤立和自发的,矛盾的焦点围绕的是单个工厂、村庄或者市区的状况。把这些斗争在更广泛基础上联合起来的努力在增加,例如在辽宁省沈阳市,整个城市所有工厂的代表就集合在一起;甚至在某个特定的地区,工人和农民之间的联系也在发展。不过截至目前,这些斗争整体而言很少配合。因此,中国当局及其支持者主要担心的,是那些更具战略眼光,目标不是在当地发动抗议活动,而是挑战整个“资本主义的”改革体制的那些人取得对目前抗议活动的领导权。已经有迹象表明,配合也在不断增加,“在网上信息交流的助力下,抗议活动日益摆脱自发自为的状态” 。在广东省太石村,有数百名村民静坐绝食,抗议征用他们的土地用于房地产开发。他们的抗议得到了一个“民主活动分子网络”的支持,它“定期发出附有这次抗议活动信息的电子邮件,并发表村民们的声明” 。村民们要求的不只是他们的要求得到现场解决,而且包括公正、法治、民主参与和“作为国家主人……选择自己未来的权利”。(18)不过,尽管自由主义分子和非政府组织正在对中国共产党和政府的控制构成挑战,但构成最大威胁的,是与毛泽东以及社会主义革命有著历史联系的左派。

当前的中国领导人决心阻止的,是“毛泽东主义”的复兴以及左派知识分子和工人阶级的联合,而不是其他什么。他们有理由害怕。在过去五年左右的时间里,左派已在中国再度出现。尽管人数仍然很少,还处于分裂和被边缘化的状态,但他们终于又一次成为中国舞台上的重要一员。这种状况的出现,在很大程度上是受到不断增加的工人和农民斗争的推动——两者的斗争形成了新的压力,并鼓舞了各社会阶层当中的行动主义。面对“改革”时代日益严重的两极分化和腐败现象,越来越多的知识分子和大学生开始回头从毛泽东那里寻求指引,并再次与新的工人阶级运动联系起来。左派对“郑州四君子”的广泛支持就是例证。表面上,其中一名被关押的工人活动分子的释放是由于健康原因,但实际上是左派的广泛支持在其中起了作用。工人和农民正在“教育受教育者”,这一进程得到了一些犹如轶事般的证据的确认。例如,在花费大量时间对农村地区进行考察之后,一位知识分子领袖发现,他在村庄中访问的每位农民都支持毛泽东,这与城市自由主义者的态度形成鲜明对照,于是他向“左”转。同样,北京的一位改革派理论家也讲述了她是如何“回到”毛泽东那里。她说,那是因为毛泽东对“资本主义道路”的批评,在今天显得尤其正确。不只一位活动分子提到,在试图用“其他理论”解释当今中国发生的事情,但却没能为解决当前日益严重的两极分化和其他负面社会因素找到答案之后,许多人再度从“毛泽东思想”那里寻求指引。

工人阶级的斗争和当前中国社会的各种矛盾,正在迫使越来越多的知识分子向左转。在这一过程中,许多人开始“修正”他们对毛泽东遗产的“修正”看法,其中甚至包括文化大革命。这在意识形态和实际后果上都具有重大意义。一方面,有越来越多的出版物,网络和论坛致力于发表对“改革”政策的左派分析和批评。其中有些人明确表明自己是“毛泽东主义者”。但另一方面更多的人采取的是“新左派”的表达方式。与西方的“新左派”类似, 中国的“新左派”也是把马克思主义的概念与社会学和社会民主的理论混合在一起。在毛泽东去世后,有关毛泽东时代的负面解释曾经被广泛接受。而如今,尤其是青年知识分子,对这种解释提出了严重质疑。甚至是“老左派”——他们中有许多人先前至少在某种程度上从邓小平的“改革”政策中获益——许多年来也一直对党和国家的指导方针提出批评,而今他们愿意更加公开地去提出批评。上述人态度的改变,有著广泛的群众基础。例如,每年都会有大约四百万中国人前去延安访问,从“背包的大学生到成群结队乘坐公共汽车前来的中年工人”不一而足。延安,这个位于中国西北的偏远革命根据地,是长征结束的地方。在那里,毛泽东领导了抗击日本侵略的游击战争,发动了对蒋介石和国民党的最后决战。也正是在那里,中国共产党的目标得到发展和完善,从而吸引成千上万的工人和知识分子加入到毛泽东领导的革命斗争中。尽管张戎、哈利迪之流以及某些中国国内的批评家在极力批判延安的精神遗产,但也许是由于地处偏远,延安仍然是牺牲和亲民精神的一个象征。这种精神曾经是革命的标志,与当今的奢华、腐败以及对工人和农民的剥削形成对照。(19)

对于那些反对哪怕一点点毛泽东主义复兴迹象的人来说,中国早期革命阶段的复苏和延安精神的思潮令他们极为担忧。举一个现实的例子:文革结束之后,知识分子和工人阶级斗争相结合就杳无踪迹了,现在,许多青年知识分子开始左转,逐渐开始与工人阶级结盟,未来可能会对工人阶级的斗争产生巨大影响,这一现象引起了他们极大的恐慌。大约五年前,在中国一些著名大学的校园里面逐渐兴起了一些小型的马克思主义研究组织。起初他们只是彼此孤立研读马、恩、列、尤其是毛泽东的著作,现在这些组织逐渐联合起来结成了左翼校园组织网络。随着参与大学数量的增加,学生们开始与一些城市(比如郑州)的工人阶层接触,研究并报道他们的生存状态,为他们提供法律和物质方面的帮助。其中一个学生组织“农民之子”正在派遣学生前往农村地区。这些小小的组织仅仅是大学校园的一角,参加者可能正处在学习阶段或者正在工作,但这些校园组织的产生无疑是中国的一个巨大进步。成百上千的学生和那些持有激进政治思想的人通过这些活动开始积累了关于工人阶级状况和斗争的实践经验,他们甚至有的参加工人的活动,反对党和政府当局的现行政策。而自文革以来,这种形式的工学联合从未出现过。

邓小平改革之后,官方教育政策重新成为专业精英统治并且过于偏重学术成果,知识分子和工人农民之间的分裂加深了。随著学生组织的深入基层,这一分裂开始被填合,尽管这种学生组织仍旧极为边缘化,并不得不屈从政府的压制政策——某些试图进入郑州的学生被当地火车站禁止下车。因此,在当前时局下张戎和哈利迪出版这本书,有试图阻止工人阶级和左派结盟之嫌。年轻的一代必须要注意预防这种“毛泽东主义”威胁论。当前大陆已经禁止出版这本书,禁止杂志刊登该书评论,但这本书的地下版本和网络版本必然很快流传开来,因为香港和台湾已经允许该书发行了。而且该书的主要观点至少会在相对大的其追随者的范围内流传开来。

当前中国处于转型的关键时期,很显然这本书是目前民众思想斗争中一个分界线——中国到底应该彻底全球化,一头跳下资本主义的悬崖,还是应该悬崖勒马,重建一种新社会,其中社会主义者和工人阶级能够在官方政策制定上起到一种决定性的作用。目前中国阶级斗争重新浮现,各方都在积聚力量,在这个意义上,该书是一个阶级斗争的武器,作者对待革命时期阶级斗争的态度显示了该书的这一根本特性。这本书的第一章指出:在传统官僚社会中,任何人通过获得教育都可以坐到任何高位,而且任何背景的人都能得到权利和财富——这句似是而非的话掩盖了旧社会对农民的压迫和通过革命斗争来结束这种压迫的必要性。相反, 1920年代的农民起义被说成和强盗没什么区别,而毛泽东参加起义的目的被说成是增加人生经历。显然,这本书的出版是一个有预谋的战略步骤,旨在反对中国现实中正在成长的革命思想的萌芽,这种革命思想不仅仅滋生于工人阶级头脑里面,而且出现在逐渐向左转并开始与文革以来即受冷落的工人阶级结合在一起的知识分子头脑之中。为了阻止这种有组织斗争向更高层次发展,政府最近对社会进行了警告:“共产党的喉舌《人民日报》最近发布了一篇措辞严厉的社论《保持稳定加速发展》,上面警告民众必须要遵守法律,任何影响社会稳定的行为都会受到惩罚”。(20)话音刚落,一轮更为严厉的互联网管制以及其他形式的电子交流就开始了。

《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》一书并不仅仅对目前中国有意义,对其他各国也同样重要。因为促使中国向著新方向前进的这种力量同样也在影响著其他地区的工人和受教育的阶层。因此,从全球反帝反资本主义剥削斗争中的历史性地位这一角度理解毛泽东极为重要,他和胡志明以及后来的卡斯特罗同样是民族统一解放和社会主义革命中的卓越领导人。冷战(实际上是一系列连续不断的“热战”)产生的根本目的,就是防止左翼力量结盟。西方国家到处伸手,从向中国革命胜利后败逃台湾的国民党抛出保护伞,到朝鲜战争、猪湾事件、越南和拉美及非洲的无数次战争,他们试图通过干涉第三世界国家的革命,来打破反帝和社会主义联盟,慢慢包围和压制共产主义。随著苏联集团的解体,中国向资本主义的再一次转向,美帝国主义及其附庸终于松了一口气:他们已经彻底拔除了心头之刺,彻底消除了左派对其世界规则的威胁,人类历史的终点一劳永逸的彻底达到了。用弗朗西斯·福山的话说就是:

“人类意识形态停止了演化就意味著人类历史的终结”。

左派力量也不会安静地呆在坟墓中。英国伦敦的《观察家》杂志最近说,右翼报纸《每日邮报》刊登了一篇两页的文章《怪物马克思》,其中诽谤马克思是“寻找贫民收容院的人”,他“早已在1883年死去了”, 该文章是获悉英国BBC广播四台中数千听众把马克思视为他们最喜欢的思想家后,邮报做出的最强烈反应。“屠杀成性的斯大林、毛泽东、波尔·布特、穆加贝都是其信徒,为什么马克思还是被选为最伟大的哲学家呢?”(21),似乎“怪物”这个词是新近对马克思和毛泽东最合适的称谓了,因为使用这个词的人根本不能明白,为什么世界上还有那么多人对他们念念不忘。《观察家》杂志分析道:答案是资本主义在不断为左派提供复活的原料。当前世界资本主义系统中的矛盾(这种矛盾目前在中国和世界各地都普遍存在),推动著工人阶级、知识分子不断转向左倾化理解世界,因为只有这样理解世界,才能解释当前人们生活中正在发生著一些什么,才能不仅仅提供微调这种压迫体系的方案,而且提供彻底解决该矛盾的方案。因此,马克思及其信徒(包括毛泽东)有必要再一次被说成怪物,有必要从名誉上彻底打垮,以预防全球再一次左转,工人和农民再一次走向革命和社会主义。英国新闻界、张戎和哈利迪,他们的需求是相同的:召集各种力量,防止世界范围内左翼势力的复兴。

就中国而言,目前遇到的威胁, 并不仅仅是意识形态方面的。特别是第三世界国家,甚至世界上的主要资本主义国家中,每天都有数千万人在同资本主义全球化作斗争。这种斗争的具体表现比如——拉美国家左转,全球社会中最受压迫和被边缘化的本土阶层对经济恶化和环境破坏的抗议:亚洲工人和农民反对资本主义跨国公司的剥削,反对社会两极分化的斗争;非洲民众急需免除债务,急需获得治疗艾滋病的廉价药物;像最近苏格兰八国峰会那样主要资本主义国家元首集会处的大规模示威活动,等等。这些运动表明面对毫无限制的资本主义,民众已经自发组织起来,抗议资本家剥削、环境破坏、经济和社会两极分化的活动达到了空前的高潮。

但就像在冷战时期一样,这种斗争的反全球化,也即反对美国操控的帝国及公司扩张、反资本主义与支持社会主义,各方面很难统一起来。比如,世界社会论坛一直处于“全球正义”运动的最前线,但参加者和追随者(尤其是美国成员),普遍反感社会主义革命和左翼意识形态传统。其会址没有一次设置在激进主义分子和革命运动所在地,像尼泊尔和秘鲁的毛泽东主义者,哥伦比亚和菲律宾的马克思主义者的游击战,还有很难与传统斗争形式相吻合的位于墨西哥恰帕斯州的萨帕塔运动等等。甚至中国数百万工人的抗议活动,也很难引起反全球化力量的重视。一方面因为他们很难参加像世界社会论坛这样的会议,另一方面可能因为他们也被认为存在社会主义革命和毛泽东主义的残迹。(22)尽管参加全球正义运动的成员观点千差万别, 但他们都自认为是“社会主义者” 。比如2006年世界社会论坛将在委内瑞拉召开,总统查韦斯强烈支持“玻利维亚社会主义运动”。

但在反殖民主义的时代,只是在特定情况下,反对帝国主义体系的斗争和社会主义运动才统一起来,目前二者不统一仍旧是最大的一个缺陷。因此,在中国的帝国主义者及其意识形态的支持者,必然会想尽一切办法阻止工人阶级与左翼革命力量结盟,阻止全球正义运动和社会主义运动结盟。因此,目前这种已经造成反对美帝国主义世界秩序和资本主义体系的力量减弱的分裂状况,可能会进一步加深。张戎和哈利迪出版的这本书,应该被视为这场全球性斗争中,全世界右派反应的一个组成部分。它旨在想尽一切办法,阻止毛泽东所代表的反帝斗争和社会主义运动的统一,因为二者的统一有望重新兴起,越发壮大。

当然,这并不是说该书或该书评论就是这一全球性的反毛斗争的全部内容,他们仅仅是当前反左氛围中的一个组成部分,他们与那些拥有反动观点的人共享同一种意识形态,只是表达方式不同罢了。该书的出版是全球阶级斗争和意识形态斗争的一部分,它必然会导致相反的结果。该书引用的每一份攻击毛泽东的材料,尽管有菲利浦·亨舍等人的支持,但也必然会引起人们的关注和质问,到时他们将哑口无言。首先那些曾直接在毛泽东身边工作过的人员就会出来驳斥他们,毛泽东以前的同志也会表达自己的观点,捍卫毛泽东的人格和光辉业绩,就像以前人们对李志绥那样。但由于张戎和哈利迪引用了大量毛泽东的早期同事的话,这无疑是在鼓动那些持不同意见的人主动从相反的角度来理解历史事件,回忆他的工作生活。此时,历史学家和中国学者们无疑会站出来,对毛泽东时代进行客观中肯的回顾。与此同时,人们也必将会揭露出张戎和哈利迪随意的治学态度,尤其是引用来源不规范的文件,对历史事件的选择性使用和解释带看偏见、和他们自己的早期著作自相矛盾等等。这些问题并非只是左派人士才提出。一些对历史持较为客观和批判性态度的学者就早已经指出,张戎和哈利迪比以前所有苛刻评论毛泽东的人更加不负责任。“全世界的中国学者都在质疑这本书中历史账目的准确性,即便是最著名的评论家普林斯顿大学的林培瑞,23也对其中资料错误和来源不明深感有必要进行批判”。(24)《纽约时报》知名评论家克利斯托夫同样也谴责该书作者,采用一篇文章中对大跃进期间死亡人数的最高估计作为唯一正确的数据来使用。这是不应该的,否则别人也可以支持远比它们更低的数据。(25)同样是在导致很多人死亡的运动(主要是大跃进和文革)中,国家同时也为工人阶级尤其是农民引进了很多卫生保健措施和社会扶助政策,挽救并延长了数以千万计的人的生命,使中国人口寿命的延长程度和识字比率,大幅度领先了亚洲处于同样发展阶段的印度和印尼。显然,中国革命时期成绩和代价基本持平,但《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》根本不提期间任何积极的成绩。而且,随著这本书特别是在中国流传面的增大,其中的观点就会真正受到大家的考查和驳斥,

这需要长期不懈的,坚决的斗争。

但是,那些没有和毛泽东直接交往过的人,还有那些专门研究毛泽东领导历程的专家,可能会提这样一个问题:毛泽东是真正马克思主义者吗?西蒙·塞巴格·蒙蒂菲奥里在评论中说:“该书作者认为毛泽东从来不是一个马克思主义者,他只是一个机会主义者”。角谷美智子在《纽约时报》上的评论也说,“作者认为毛泽东并不真心相信马克思主义”。熟悉左派理论史的人知道,历史上关于毛泽东所力行的马克思主义的性质,一直存在争议和不同意见,尤其是关于他闹革命依靠农民军队(有人认为这和经典马列主义不相一致),他和苏联关于修正主义的矛盾,以及对西方开放等等。直到今天,世界左派阵营还常常划分为两派,划分的标志就是究竟应不应该按照毛泽东倡导的方式来理解马克思主义。张戎和哈利迪是不是有能力站在马克思主义的立场上讨论这个课题很成疑问,而且,蒙蒂菲奥里所说的话是非常荒谬的,毛泽东的著作就是对此最好的驳斥。毛泽东早年的一些著作,比如主要是建基于恩格斯、列宁理论之上的《中国社会各阶级的分析》、 《湖南农民运动考察报告》为农村革命提供了理论和实践上的指导,

后来的土地革命同样也是根据于此。从他勾勒出打败日本侵略军的阶级联盟到在延安文艺座谈会上的讲话,再到晚年著作陈述中国向社会主义转型期间意识形态领域的不断革命理论,这些都不仅完全根基于马克思主义基本理论,更是对马克思主义理论的重大贡献。他奉献给中国和世界上所有左翼人士的理论文献比如《矛盾论》,是对马克思主义辩证法的深化和拓展。毛泽东的这些著作也对美国各种各样的组织团体产生了—巨大的影响,比如比较激进的妇女解放组织“红袜子”、黑豹党和各种学术团体、职业团体等等。毛泽东使马克思主义理论从书斋真正走向了数亿工人和农民,这是他的伟大成就。

显然,张戎和哈利迪讲毛泽东“根本不是一个马克思主义者”,这仅仅是他们对毛泽东的妄自猜度,他们的本意是想借此消除毛泽东的影响。他们说毛泽东的《湖南农民运动考察报告》仅仅是毛本人出于对暴力偏爱的凭空想像。对于毛泽东分析中国乃至世界范围内的阶级斗争和政策冲突的文章,他们不是去深入考察分析,而是以同样浅薄的态度直接否定。一些较为中肯的分析家比如詹姆斯·哈特菲尔德早就注意到该书中普遍存在的偏见和恶毒的敌意,他不可能逐一驳斥该书的所有结论,于是就通过详细调查揭露了其中包含的对事实的歪曲。他在评论中指出了张戎和哈利迪文章在事实和方法论上存在的缺陷,尤其注意到他们“拼命用他们‘所不知道的故事’来解释毛泽东的胜利,因为他们为达目标根本不考虑自己的信誉” 。(26)角谷美智子也指责说,该书作者参考能够清晰反映毛泽东政治观、价值观的毛著太少,导致该书历史背景缺乏,充满偏见和简单化。克利斯托夫抱怨说,在这本书中,“毛泽东是一个历史上偶然出现的恶棍,是一个装模做样的偏执狂,完全没有作为一个真实的历史人物的立体形象,因此使人难于理解毛泽东怎么能够战胜对手而成为中国领袖和成为历史上最受崇拜的偶像”。这些都是张戎和哈利迪之流妄图贬低毛泽东的根本漏洞。这样贬低毛泽东根本不能解释中国革命胜利的原因,根本不能解释这样的领导人如何能够领导世界历史上规模最宏大的、绵延近半个世纪的、涉及五分之一到四分之一世界人口的、推翻了几千年来中华帝国一直沿袭的阶级结构、打败了国内敌人和国外帝国主义势力、以最为深刻的方式改造了数亿工人农民生活方式的革命斗争取得成功!

这种把历史变迁看作主要是一个伟人的作用(在这本书里面是一个恐怖而邪恶的人),

贬低了中国人民的智慧和中国人民的革命斗争,尤其是贬低了跟随毛泽东历尽千难万险、尝尽胜利和失败、取得了巨大成就但也遭受了沉重损失的中国工人阶级。该书作者也不懂得社会变革的复杂性,尤其是在中国革命这个水平上的变革和领导这场变革的人的艰难。毛泽东作为一个革命领袖,他和当时所有的革命家一样,身上有极其强烈的革命精神,但他是一个人,他是其时代和文化的产物,因此不可避免地受到当时中国社会的局限,具有自己的优缺点。毛泽东的历史纪录是中国几十年革命斗争的主要线索,必须在中国自身及其塑造毛时代的世界性力量的背景下不断加以回顾和研究。这一回顾和研究中的主要组成部分必然包括两块:中国革命所取得的巨大胜利和所付出的沉重代价。但是,像张戎和哈利迪这样把毛泽东贬低成一个单纯的怪物,必然不能真正解释历史,只能是沦为一个空洞而扭曲的政治宣传。

在一些较为中肯的评论网页上,在一些左翼网站和左翼人士的电子邮件上,批驳《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》这本书的运动早就已经开始了。但是我们注意到,站在左翼的立场上的知识分子和新闻记者很多属于政治社会主流,反对张戎和哈利迪的全部或部分观点,反对他们对事实的歪曲。但他们是处于相对弱势的一方,因为他们无力抗衡右翼垄断集团和大出版商的出版物和电子媒体,准政府性质的全球无线电网络(比如覆盖面每日达到数亿人的BBC)。与这种对手相比,左派资源明显处于劣势。反动派认为通过这种攻击可以最终赢得胜利,但这场战斗不应该也不会仅限于反动派设定的这种战场上,因为读过这本书,赞成或者反对该书观点的人,并不能决定这场战斗的最后胜利。毛泽东早就指出:“人民,只有人民,才是创造世界历史的动力” 。(27)这里仅需要变成:人民,尤其是数亿工人阶级是该战斗的最终仲裁者。最后,只有中国人民整体,首先是工人和农民乃至与他们站在一起的全世界数亿工人农民,才能最后做出历史性评判,才能评判毛泽束是否让他们生活变得更好或者更坏。如果有人肯花费一丁点时间去与中国工人阶级进行交谈就会知道,他们直到今天都对毛泽东和毛领导的社会主义革命心存感激和认同,仍旧把毛泽东视为他们的代表,而没有一点犹豫和反对。当他们把毛泽东时代的统治者和现在的统治者相比较时,这种思想更甚,因为他们认为现在统洽者更多是腐败分子,更多是党内国内日益上升的剥削者阶级的代表,是快速冒起的资本家阶级的代表,他们只是日益把工人和农民逼向绝望,逼向公开暴动的边缘。前中国政府顾问,《人民日报》评论员、现在加拿大维多利亚大学教授政治科学的吴国光指出,“群众不满的根源主要是共产党官员的滥用权力,如果政府廉洁而高效,国内就会平静得多。但问题是政府官员并不考虑国家的利益,他们在想方设法追求自己的利益——别管是合法的还是非法的”(28)

要想彻底驳斥张戎和哈利迪的攻击, 除非把深藏于工人阶级之中的巨大感情和记忆宝藏开发出来,否则是很难成功的。但在中国,由于对工人阶级的教育系统瘫痪,绝大多数工人根本无缘见到《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》一书。然而,他们根本没必要通过看这本书来评价毛泽东及其领导的革命。他们的生活、他们直接的感觉都告诉他们,毛泽东领导时期工人阶级的权利和地位,免费教育和卫生保健、就业机会和社会保障,工厂或农场运行管理的参与权,这些权利现在已经基本失去了。因此, 我们必须要发动一切力量,帮助中国工人阶级表达出自己对毛泽东及其遗产的真实观点:首先就是毛泽东领导的革命斗争,特别是文化大革命,旨在帮助工人阶级创造机会,成为历史发展和社会的主人,最终从几千年受“教育阶级”的统治下解放出来,最初是从满清官僚的统治下解放出来,进而即便是共产主义胜利之后,也要从那些把人民群众视为无知群氓的党政官员乃至知识精英的统治下解放出来。要想捍卫毛泽东,我们必须要以他为榜样,致力于帮助并推动中国工人在新的时代条件下进行阶级斗争。毛泽东在晚年早巳预见到并一直试图防止中国资本主义化,但是“经济全球化”的推动恰恰已经使中国开始资本主义化了,工人阶级在这一进程中,必须要通过斗争重新做出自己的角色定位。

因此,这是一本恶毒有害的投机性著作,它暴露的问题是连反对毛泽东的人,甚至是称毛泽东为恶魔的人都难以接受。因此,“世界上一些最著名的研究近代中国历史的学者认为张戎的这本书根本是在歪曲历史” 。早期的一些评论认为:

人们都认为已故中国共产党主席毛泽东是一个恶魔,他把他党内同志乃至整个中国都推进了地狱之中。这是一本极为有力必然会产生广泛影响的书。

很多人认同纽约哥伦比亚大学波恩斯坦(ThomasBernstein)的观点:“这本书对于现代中国研究领域而言是一个巨大的灾难”。

他这周说:“该书拥有数量巨大的参考资料,因此其观点将会被广泛接受,但其内容主要服务于彻底摧毁毛泽东的个人名誉”。

“……数量同样巨大的脱离背景的引用语、对事实的歪曲,而且对于毛泽东如何成为一个复杂的、充满矛盾的多面领导人的描述过于罗嗦”。(29)

英国牛津大学的史蒂夫·唐说, “该书作者在证据来源上的不诚实令人恐怖”,

“毛泽东确实是个恶魔,但该书作者把随意扭曲的历史作为证据来贬低毛泽东,最后将会难以揭示毛泽东和中国共产党系统是多么可怕, 他们究竟对中国人民做过多少恶” 。意大利《新闻报》的著名记者郗士指出,“在该书中,你看不到冷静客观的分析,你只能感觉到一种憎恨,这使该书成为一本好的读物,但历史根本不是这样的”。悉尼大学的费雷德·特韦斯在张戎写这本书的时候见过她:“她固执地坚持自己的观点,根本不愿接受别人的意见和不利的证据”。他评论毛泽东说:“如果说有人必须——我认为是毛泽东——要为超过三千万人的死亡负责,这一点难以辩驳。但是如果仅仅是把他描述成为一个彻头彻尾的恶魔,他的出现就是为了不惜一切代价保护自己的权力和杀人,那相对于现实而言就有点过分甚至是疯狂了”。

毛泽东曾经预言,敌人的攻击必然会无所不用其极, 最终会犯下致命的错误失去民众的信任。一种盲目研究分析可能带来暂时战术上的胜利,但从长远战略上看来是愚蠢的,

最终只能导致那些反对革命变革人们的内部矛盾加剧。因此,《毛泽东:鲜为人知的故事》书中对毛泽东的攻击, 一方面代表著一种恐吓,另一方面也代表一种机会。这本书尽管有一定的破坏力,但也无意中说明了毛泽东和他领导的社会主义革命的重要地位,正好说明了当前毛泽东的思想和政见再一次变得极为重要,说明了工人阶级正在以新的反叛形式崛起。对于那些把毛泽东视为怪物的人来说,该书无疑为他们提供了新的证据。但恰恰是他们的著作“使我们不仅清楚划分了敌我界限,而且使我们工作获益良多” 。反动派是如此无所不用其极地憎恨和歪曲毛泽东,反倒使我们不再相信他们曾经走过的路,不再相信那些持这种观点的人,也必然会呼唤对毛泽东历史地位的客观积极评价的回归。重新评价毛泽东,打开了那些长期关闭的门,尤其是使我们重新想起了他的警告:如果中华民族从社会主义道路上重新回到资本主义道路,后果将会是什么?

显然,在这里问题的关键并不是重新恢复毛泽东的个人名誉,不是他在过去革命斗争中处于如何重要的地位。问题的关键在于中国人民乃至世界人民是否会重新走向社会主义。全面公平评价毛泽东历史,有助于重新提出这个问题, 并给出一个圆满的回答。在这个意义上,张戎和哈利迪的攻击“是好事而不是坏事”。前提是中国乃至世界上支持社会主义革命的人,是否能充分把握、该书出版所提供的机会,

重新致力于毛泽东所提出并毕生力求实现的目标,致力于从事他曾经领导的全球工人阶级的斗争。这在今天和他活著的时候,都同样重要。

注释:

(1) 作者罗伯特·韦尔(Robert

Weil)是两个加州大学校园的演讲人与图书馆员联合会的组织人,发表过多篇论及中国经济、政治及劳工状况的论文,著有《黑猫白猫:中国及其“市场社会主义”的矛盾》 (Red Cat,White Cat:China and the Contradictions of“Market Socialism”,美国《每月评论》出版社1996) 。

(2) 全文译自Robert Weil:“To be attacked by the enemy is a good thing”,http://www.chinastudygroup.org。原文出处“中国研究组” (China Study Group)是1995年成立于纽约的一家非盈利机构。文章由伦敦经济和政治学院林春推荐。副标题为编者所加。

(3) 毛泽东:《到韶山》, 《毛泽东诗词》,北京外文出版社1976,第36页。

(4) 《被敌人反对是好事而不是坏事》,1939年5月26日。

(5) 菲利普·亨舍,www.seattlepi.com,2005年6月8日。

(6) 乔纳森·米尔斯基: 《毛泽东神话的延续》, 《国际先驱论坛报》,2005年7月6日。

(7) 伦敦《星期日泰晤士报》,2005年5月29日。

( 《纽约时报》,2005年10月21日。 《纽约时报》,2005年10月21日。

(9) 《纽约时报·书评》,2005年10月23。

(10) 《掷向毛泽东的书》,www.theage.com.au,2005年10月6日。

(11) 《掷向毛谭东的书》,www.theage.com.au,2005年10月6日。

(12) 《纽约时报》,2005年7月24日。

(13) 《华盛顿邮报》,2005年7月10日。

(14) 美联社,2005年9月21日。

(15) 美联社,2005年9月21日。

(16) 《纽约时报》,2005年8月24日。

(17) 《纽约时报》,2005年8月24日。

(1 理查德·麦格雷戈:《胡在尽力使中国摆脱农民起义》《金融时报》2005年9月7日。 理查德·麦格雷戈:《胡在尽力使中国摆脱农民起义》《金融时报》2005年9月7日。

(19)《纽约时报》,2005年7月1日。

(20)《纽约时报》,2005年8月24日。

(21)《怪物马克思》《每日邮报》2005年6月17日。

(22) 约翰·久利克: 《中国工人农民的暴动》,埃迪·于、丹尼尔·伯顿——罗斯、乔治·卡茨菲克编:《对抗资本主义:全球运动一览》,纽约软骨出版社2004年。

(23)《天安门档案》编者之一。

(24)《掷向毛泽东的书》:www.theage.com.au,2005年10月6日。

(25)帕特耐克的演讲:《饥饿的共和国》,新德里2004年4月1日。

(26)詹姆斯·哈特菲尔德:《毛泽东:事件的终结》,wvvw.spiked-online.com,2005年7月4日。

(27)毛泽东:《论联合政府》,1945年5月24日。

(28)《纽约时报》,2005年8月24日。

(29)《掷向毛泽东的书》,www.theage.com.au,2005年10月6日。

|

|

| 返回页首 |

|

|

hgy818

注册时间: 2007-09-13

帖子: 1298

|

发表于: 星期日 十一月 11, 2007 9:19 pm 发表主题: 罗伯特.威尔:“被敌人攻击是一件好事” 发表于: 星期日 十一月 11, 2007 9:19 pm 发表主题: 罗伯特.威尔:“被敌人攻击是一件好事” |

|

|

To be Attacked by the Enemy is a Good Thing

by Robert Weil

http;//www.chinastudygroup.org/index.php?action=front2&type=view&id=69

I have always considered the words of Mao Zedong, "To be attacked by the enemy is not a bad thing but a good thing" to be among his most valuable. Not only did it alter my conception of struggle, but it encapsulated perhaps more succinctly than any other of his sayings, the profoundly dialectical character of his thinking and strategy. It was this quality that allowed Mao to exploit the contradictions among the enemy, to "overcome all difficulties," and to turn defeat into victory over and over again. But it was not the losses and suffering that such attacks brought that Mao was referring to—what he called the "bitter sacrifice" that revolution required, though he was always determined to turn it into "bold resolve" ("Shaoshan Revisited," in Poems, Beijing; Foreign Languages Press, 1976, 36). The reason that to be attacked was a "good," and not a "bad" thing, was that it meant that the revolutionary forces were hurting the enemy, were a challenge to their control, were successfully carrying out the struggle. Otherwise, why would those opposed to the revolution even bother to attack? The less restraint such enemies showed, the more it revealed their own weaknesses and blinded them to reality. "It is still better if the enemy attacks us wildly and paints us as utterly black and without a single virtue; it demonstrates that we have not only drawn a clear line of demarcation between the enemy and ourselves but achieved a great deal in our work" ("To Be Attacked by the Enemy is Not a Bad Thing But a Good Thing", May 26, 1939). The more strongly the revolutionaries were attacked, therefore, the higher the measure of the success that they must be having, in order to cause such a response from their enemies. Moreover, a blind thrashing out by those opposing the revolution, guided only by hatred, would cause them to make serious errors and discredit them in the eyes of the people.

The recent publication of Mao; The Unknown Story, by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday, is an unrelenting and painful attack, not only on his leadership as an individual, but on the entire history of the revolution that he led, and on the ongoing struggle for socialism not just in China, but globally, of which it is such a fundamental part. Just released in the United States—it was earlier available in England and Asia—a sense of its overall approach and tone can be quickly grasped from even a cursory first perusal of the text. But the nature of this work had already been apparent from a reading of excerpts on the BBC program "Off the Shelf"—more commonly devoted to fiction—where it was clear that every action and event in the life of Mao have been treated to the most negative possible interpretation, a view confirmed in an interview with the authors on National Public Radio on October 20, 2005, and another on BBC five days later. This quality of the character of the book was evident as well from the early reviews already published before its U.S. release. As these reviewers universally made clear, the book sets out, in great detail, not only to demolish Mao as both a leader and as a person, but to deny the very nature of the Chinese revolutionary socialist past, down to the smallest factual matters. In it, the principal guide of both the national liberation struggle and revolution for socialism of the people of China is portrayed as a coward, scornful of the peasants, who enjoyed the deaths the revolution brought, ruled only through fear and manipulation, and was personally dissolute. It is already being seized upon by both mainstream and at least some "new China hand" reviewers with even more enthusiasm than they earlier embraced the supposed expose, The Private Life of Chairman Mao, by "Mao's Doctor," Li Zhisui. This breathless eagerness in the reception accorded the new work extends to the BBC, which gave Mao; The Unknown Story, though it claims to be a book of well researched nonfiction, a "dramatic" reading in a voice dripping with cynicism and irony.

The written reviews have a similar quality of unquestioning enthusiasm. In what one of the reviewers calls "a work of unanswerable authority . . . Mao is comprehensively discredited from beginning to end in small ways and large; a murderer, a torturer, an untalented orator, a lecher, a destroyer of culture, an opium profiteer, a liar" (Philip Hensher, www.seattlepi.com, 6/8/05). Claiming that he was responsible for 70 million deaths—an assertion vastly out of proportion with even the highest and hotly disputed claims put forth by some others—"Chang says of Mao, 'He was as evil as Hitler or Stalin, and did as much damage to mankind as they did'" (Jonathan Mirsky, "Maintaining the Mao Myth," International Herald Tribune, 7/6/05). But even this is not enough for some reviewers. Comparing him to the former Russian leader, Simon Sebag Montefiore declares, "Mao is the greatest monster of them all – the Red Emperor of China" (The Sunday Times – Books, London, 5/29/05). Philip Hensher joins this chorus of initial and enthusiastic reviewers, using similar language to denounce the "whole monstrous saga." The first reviews in the United States following its release there parrot this language, with "China's Monster, Second to None," the title of the review in the New York Times by Michiko Kakutani, who notes that the book makes "an impassioned case for Mao as the most monstrous tyrant of all times" (10/21/05). The same words were echoed two days later—the lack of any originality in their language is itself telling—in the Times Book Review by Nicholas D. Kristof, who despite expressing doubts about its scholarship, sourcing and accuracy, and "reservations about the book's judgments, for my own sense is that Mao, however monstrous, also brought useful changes to China," nevertheless declares it to be a "magnificent biography" and a "magisterial" work. (10/23/05, 1, 10).

Hatred of Mao simply reeks from the pages of most of these reviews. They serve, intentionally or otherwise, to intimidate any who might take a positive, or even just a less totally negative view, than do Chang and Halliday, of the life and accomplishments of the leader of the Chinese socialist revolution. It is therefore important to address the climate out of which Mao; The Unknown Story and those who have so eagerly embraced it come and to which they in turn contribute. Clearly, this work fits perfectly into the pattern that Mao himself already anticipated in his essay, "To Be Attacked by the Enemy . . . ," as it "attacks us wildly and paints us as utterly black and without a single virtue." It is this entirely one-sided approach that the majority of reviewers have eagerly embraced and unquestioningly adopted as their own, blinding them to any more balanced analysis of his role. Like many others, I responded with anger and dismay at the issuing of this "poison weed," as Professor Mobo Gao of the University of Tasmania in Australia has termed Mao; The Unknown Story—the book, as well as the many laudatory reviews of it, are already being challenged and disparaged by some initial readers, both Chinese and Western, on the web and elsewhere. But once my immediate reaction had passed, I was left with the more basic question; Why this book, and why now? If "to be attacked by the enemy is not a bad thing but a good thing," what is it about Mao, almost thirty years after his death—when the current leaders of China have turned the socialist revolution that he led on its head, and returned to the "capitalist road" that he both foresaw and tried to prevent them from taking—that is still so threatening today? Why do the enemies of Chinese revolutionary socialism, such as Chang and Halliday, as well as their publishers, Jonathan Cape and Alfred A. Knopf, feel the need to trash his legacy, and to do so more completely than ever before? Why do so many reviewers outside of China feel the need to eagerly embrace their book? What about Mao is so relevant to the contradictions and struggles in Chinese society and the world today to call forth such attacks?

One cannot discount purely personal and financial elements here. For Chang, the author of the familial autobiography Wild Swans, Mao, and particularly the Cultural Revolution that he led, continue to be a source of deep bitterness and cause for revenge. That book focused in particular on the disillusionment and sense of betrayal both the parents of Jung Chang, and later she herself, felt after their earlier unquestioning and enthusiastic embrace of Mao. This personal history lies at the heart of the new work.

Driving the book is an unrelenting hatred of Mao Zedong, and a determination to pile up evidence to blacken him as totally selfish and sadistic—particularly by Chang, who as a teenager was an enthusiastic Red Guard at the start of the Cultural Revolution but who turned when she saw her academic parents brutally persecuted (causing the death of her father). ("Throwing the book at Mao," www.theage.com.au, 10/6/05)

This is an old pattern. As those familiar with the tradition of such literature know, it is often from among the most fervent revolutionary believers, that the most scathing attacks come after they have "turned." An element of personal vendetta cannot be dismissed in considering this new work. But Wild Swans, which sold some 10 million copies, was no doubt also immensely rewarding financially. Today Chang "lives in great comfort in London's plush Notting Hill from the proceeds of her worldwide bestselling book" ("Throwing the book at Mao," www.theage.com.au, 10/6/05). Presumably there are hopes that the new work will repeat that success, both for the authors and the publishers.

Yet obviously more is at stake here than simple personal rewards, whether emotional or financial. A book like Mao; The Unknown Story, clearly has a political purpose. For those who are filled with hatred for the Chinese Communist revolution—whatever form it may take—it is not enough that the leaders of China today have largely disassociated themselves from Mao and reversed his policies. They still call themselves "Communists," and it is his picture that continues to hang from the most prominent symbolic center in the entire country, Tiananmen. It is his legacy on which the current leaders even today largely depend for their waning legitimacy. As Jonathan Mirsky asks in regard to the Chinese leadership at present, "Why, then, protect the Chairman now? Because without Mao a black hole would gape beneath the feet of the Communist Party . . . Without Mao, his heirs – for that is what they are – would be left dangling in an ideological void." Mirsky, the former East Asia editor of the Times of London and another of the enthusiastic reviewers of the Chang and Halliday book, continues, "So to demolish the Chairman would be catastrophic for the present leadership. These leaders, after all, continue to emphasize that 'the Communist Party makes mistakes but only the Communist Party can correct them.' . . . But what if the Party itself is a mistake and Mao a yet greater one? China's leaders are determined to prevent that thought from getting loose in the minds of hundreds of millions of Chinese." But that, of course, is a major reason why Mao; The Unknown Story had to be written. For not only anti-Communists like Chang and Halliday, but many reviewers, his very name must be extirpated, and even the pro forma ties of the current leaders to his memory must be broken, so that China will again be "free" of any remnant of the revolution that he led and the goals that he sought.

But why do they care? How does Mao still "hurt" the enemy so much, that they feel the need to devote such effort to launching this unprecedented outpouring of hatred and bile, distorting beyond recognition the very history of the revolution that he led? To what end must even the smallest details of that struggle be denied? Why must Mao be turned into a "monster" more terrible than any other world leader? Why is his role still so central that it is "good," and not "bad," that he is being attacked? Finally, how can those who still believe in the goals of the socialist revolution in China meet such attacks with the kind of dialectical response that allowed him to turn the tables, despite setbacks and reversals, on its enemies? The answer lies in part in understanding that the attack from Chang and Halliday is a measure of how much Mao still represents the Chinese people even today. China is rising, and the entire world is struggling with how to adjust to this new reality. U.S. and British imperial leaders, in particular—and their hangers-on in the academy and the mass media, such as Chang and Halliday—are torn, as the West has always been, between viewing the rapid growth of Chinese power as an opportunity or a threat. On the one hand, the desire to exploit the vast market that is developing in China is irresistible to global capitalists. On the other, they fear not only its economic power, but the political and military might that is rapidly growing in parallel with it.

This is a constant theme in mainstream media in the United States today—not only on the right, but among liberals and progressives as well. The San Jose Mercury News expressed this in a July 17, 2005, headline, "China's Century Taking Shape." The following article, by Tim Johnson of Knight Ridder has as its lead, "If the 20th was the American century, the 21st may belong to China. Just five years into it, China has become the world's third-largest trader, one of its fastest-growing economies, a rising military power in northeast Asia and a global player extending its influence in Africa, the Middle East and Latin America." (1A) The New York Times followed with its own expression of concern, "Who's Afraid of China Inc.?," explaining how even "avowed free traders" are beginning to worry about its threat to U.S. "national security" (7/24/05, Sect. 3, 1) Similarly, columnist Robert J. Samuelson, discussing the recent Chinese bid for California oil producer UNOCAL—which was abandoned after it became clear that U.S. political resistance would block it—says that "We cannot decide whether China is a threat or an opportunity, and until we do, every discussion of our relations seems to slide into confusion and acrimony" (The Washington Post, 7/10/05). A similar ambiguity is very well expressed in the June 27, 2005, issue of Time magazine, in a lengthy Special Report titled "China's New Revolution; Remaking our world, one deal at a time." The subheadings reflect the fear as well as opportunities; "Here Comes China! Will the rise of the People's Republic mean the decline of the U.S.?" and "The People's Republic has embraced the modern world as never before. Is that cause for celebration or anxiety?"

For those for whom the answer is more threat than opportunity, it is bad enough that even a capitalist China will challenge the United States for global supremacy. But the danger will be that much greater if the Chinese should refuse to abandon their history, and once again take the path to socialist revolution, thereby threatening not only the U.S. led empire, but the very foundation of global capitalism itself. China must therefore be "cleansed" of its revolutionary past, to the point where not even a tiny remnant of it remains, and its "New Revolution" must be a safely "American-style" one, that is, devoted only to "free markets" and "deals," not to socialism and the working classes. But here a problem arises. It is not the image of Deng Xiaoping, who introduced "market reforms" after the death of Mao, much less that of the current President Hu Jintao, that Time felt compelled to put on the cover of their Special Report. Rather it is the face of Mao that they chose to represent China, complete with rays of the sun radiating from his head—a representation that was popularized during the years of the Cultural Revolution. Since he stood on the platform of Tiananmen in October 1949 and declared, "the Chinese people have stood up," he has remained the symbol of the modern emergence of China, and it is therefore over his legacy that the struggle must be waged as to what its character will be, opportunity or threat, friend or foe. For those, like Chang and Halliday, for whom the revolution led by Mao represents the greatest of evils and dangers in the modern world, it is critical that his role as the symbol of the nation is shattered once and for all. The "New China" that is emerging must therefore be swept clean of his example and turned into a pale imitation of the West that fits smoothly into the U.S.-dominated world empire and capitalist "globalization." Anglo-American "freedom," in this view, represents the Promised Land to which Jung Chang was finally able to escape at the end of Wild Swans. Only if Mao is demonized and the very nature of the revolutionary socialism for which the Chinese fought under his leadership is not just discredited, but totally denied, can the image of the nation finally be freed from the taint of "Maoism" that still haunts it today, and its people too experience Western-style "liberation."

Though research on Mao; The Unknown Story began shortly after the publication of Wild Swans and was ten years in completion, the release of the book by Jung and Halliday, therefore, comes at a time when the very character of China is a matter of not only national, but global debate, and it is only in the context of this struggle that their attack on Mao can be properly understood as just one small part of a larger conflict. But it is not just the image of the Chinese nation that is at stake. Though Mao both led and represented the national revival of China, for which he is deeply honored by its people, regardless of what class they belong to, his role as the leader of its socialist revolution is even more critical to the contradictions of today. It is not just the Chinese nation that is rising up, but the workers and peasants themselves who are increasingly rebelling against the capitalistic exploitation of the "reform" era. For many members of the working classes in China, the older of whom still hold onto personal memories of life during the time when socialism was the foundation of national policy, Mao continues to represent the possibility of a society free from the exploitation, loss of jobs and social securities, and vast polarization and corruption of the "reforms." But this is not merely nostalgia for the past or a vague sense that things were better in the "good old days." Mao remains a critical reference point to which, over and over again, workers and peasants of China can and frequently do turn in order to find inspiration and guidance in their struggles.

This relationship is not, of course, lost on the Chinese leaders. As conditions for millions in the working classes continue to worsen, even the official press in China has been forced to confront the growing polarization, and the specter of revolution past.

The gap between China's richest and poorest citizens is approaching a dangerous level and could lead to social unrest, state media reported . . . citing a government study.

The most affluent one-fifth of China's population earn 50 percent of total income, with the bottom one-fifth taking home only 4.7 percent, said the report by the official Xinhua News Agency . . . .

"The income gap, which has exceeded reasonable limits, exhibits a further widening trend. If it continues this way for a long time, the phenomenon may give rise to various sorts of social instability," it said.

These days, the wealth gap is evident everywhere, from elderly citizens digging through downtown trash bins for plastic bottles to recycle to migrant shacks squeezed between luxury villas in Shanghai's suburbs. (Associated Press, 9/21/05)

But social unrest is not just potential, as Xinhua tries to imply. It is already extremely widespread. The possible consequences are evident to the government news agency, which knows that memories of the socialist revolution are never far beneath the surface in the consciousness of the Chinese working classes. Thus even in its coverage of the study,

The language harkens back to the revolutionary era of Mao Zedong, when the Communist Party nationalized private business and seized land from wealthy farmers in one of the most extreme leveling campaigns ever undertaken. (Ibid.)

Today, as privatization is again officially promoted, and peasants confront rural officials and entrepreneurs who conspire to rob them of their lands, the potential for a turn toward more revolutionary struggle is once more in the air, striking fear in the leaders in Beijing.

Though largely ignored in the West, some of the largest working class protests anywhere in the world are taking place on a virtually daily basis across China, from the strikes in foreign owned export factories of the southern coastal areas and demonstrations in the industrial "rust belts" of the central and northeastern provinces, to revolts over corrupt officials and environmental disasters in suburbs around eastern cities and isolated villages in western rural regions. Noting that, in figures released by the Minister for Public Security, "mass incidents, or demonstrations and riots," rose to 74,000 in 2004, up from just 10,000 a decade ago, and 58,000 in 2003, the New York Times reported,

For reasons that range from rampant industrial pollution to widespread evictions and land seizures by corrupt local governments in cahoots with increasingly powerful property developers, ordinary Chinese seem to be saying they are fed up and won't take it any more.

Each week brings news of at least one or two incidents, with thousands of villagers in a pitched battle with the police, or bloody crackdowns in which hundreds of protesters are tear-gassed and clubbed during roundups by the police. And by the government's own official tally, hundreds of these events each week escape wider public attention altogether (8/24/05, A4).

These demonstrations have extended into the very heart of the "market reform" regions, such as downtown Shanghai, the new center of Chinese commercial capital. In these struggles, workers and peasants alike often contrast the ideas Mao advanced and the socialist policies he helped to introduce with the degraded conditions of their lives today.

In one protest, middle-aged residents invoked rebellious slogans from their youth during the Cultural Revolution, reportedly saying things like 'to rebel is just' as they denounced summary evictions to make way for high-rise developers and demanded fair compensation (New York Times, 8/24/05, A4).

But regardless of whether they explicitly invoke his name or not, it is Mao who provides a historical alternative in both analysis and practice to their current situation, and a point of unity for all those who oppose the present capitalistic and corrupt "reform" policies.

One example of this is the widespread support demonstrated for the "Zhengzhou 4," worker activists in that city in central Henan Province, who distributed a leaflet denouncing the current direction of the party and state at a memorial celebration on the 28th anniversary of his death. It is Mao who they invoked in contrast to the rampant capitalism and corruption of the present leaders, calling on them to return to the socialist path which the country had pursued while he was alive, a "crime" for which two of them were arrested and sentenced to three years in prison. But these four activists are by no means isolated. Leftists came from all over China to show solidarity outside of their closed trial, websites published lengthy discussions of the case and defenses of their actions, and more than one hundred Chinese—a very large number given the political risks and restricted communication channels—signed a petition letter protesting their imprisonment, joined by an equal number of those outside the country, an unprecedented international alliance in support of militant leftist workers there. But there are other signs as well of the ongoing refusal to let the struggles of the past die. In a park in a working class neighborhood in Zhengzhou, hundreds—and up to a thousand or so on weekends—gather each evening to sing the old revolutionary songs and to uphold the legacy of the Mao era. In a similar, if less developed vein, workers and peasants often express the same kinds of views; life was different and better in the period under Mao, before China took the "capitalist road" that he warned against. Of course, such attitudes are far from universal. There are some workers and peasants who are "making it" under the current "reforms," and even a few who are "getting rich," as Deng Xiaoping urged them to do. Young members of the working classes, in particular, who do not have memories of the socialist era, are increasingly being drawn into the consumer world of China today, where individualistic economic pursuits are the overriding purpose of life. But enough workers and peasants still find in Mao the inspiration for their struggles to provoke a very harsh response—as exemplified by the case of the Zhengzhou 4—not only from party and state authorities, but from all those who fear a return to the socialist policies that he advanced, and the class struggles that he led, and above all, the Cultural Revolution, the last great campaign that he initiated to keep the Chinese from turning back to the "capitalist road."

With protests growing ever larger, such social contradictions are rapidly rising. But it is not simply the expanding struggles of the working classes that are at issue here. So far, most of these demonstrations and even violent riots have been quite isolated and relatively spontaneous, focused around the conditions in an individual factory, village or urban neighborhood. Though efforts are growing to link up these struggles on a wider basis—for example, by bringing together representatives of all the factories in a city, as has taken place in Shenyang in Lioaning province, or even by developing ties between workers and peasants in a given region—there is overall little coordination so far. The great fear of the authorities and their supporters, therefore, is that the current protests will begin to be led by those with a broader sense of their strategic possibilities, and who have as their goal not local protest, but a challenge to the entire system of capitalist "reforms." There are already signs of growing coordination, as "the protests are increasingly feeding off each other, powered by information exchanges through the internet." In Taishi village in Guangdong Province, a sit-in and fast by hundreds of peasants protesting the confiscation of land for property development, have been supported by "a pro-democracy activist network" that "issues regular e-mails with information about the campaign and statements from the villagers," who are demanding not only that their immediate claim be addressed, but justice, the rule of law, democratic participation, and the right "as master of the country . . . to choose our own future" (Richard McGregor, "Hu at pains to keep China from peasants' revolt," The Financial Times, 9/7/05). But though liberal activists and NGO's such as these pose a growing challenge to state and party control, it is the left, with its historic ties to Mao and the socialist revolution, that poses the greatest danger.

More than anything else, what the present leaders of China are determined to prevent, is a revival of "Maoism," and the linking up of leftist intellectuals with the working classes. They have reason to be afraid. Over the past five or so years, the left has reemerged in China, still small, divided and marginalized, but once again becoming a significant part of the national scene, driven in large part by the growing struggles of the workers and peasants themselves, who are both creating renewed pressure and providing inspiration for activism among all social strata. In increasing numbers, intellectuals and university students, in the face of the growing polarization and corruption of the "reform" era, have begun to turn back to Mao for guidance, and to link up once again with the new working class movement—as exemplified, once again, by the widespread leftist support for the Zhengzhou 4, which may have contributed to the release of one of the imprisoned activists, ostensibly for health reasons. Anecdotal evidence confirms this process, in which workers and peasants themselves are "educating the educated." One leading intellectual, for example, turned to the "left" after spending extended time in the rural areas, because every person he met in his visits with peasants in the villages supported Mao, in contrast to the attitudes of urban liberals. So too, a progressive academic in Beijing, told how she was "moving back toward" Mao, because his critique of the "capitalist road" rings increasingly true today. As more than one activist put it, having tried "everything else" to explain what is happening in China, without finding answers for the polarization and other negative social factors becoming ever sharper by the day, many are turning again to "Mao Zedong Thought" for guidance.

As a result, both the struggles of the working classes, and the contradictions of the current conditions of Chinese society, are compelling more and more intellectuals toward the left. In the process, many have begun to make a "revision of the revision" of their view of the legacy of Mao, and even of the Cultural Revolution. This has significant ideological and practical consequences. On the one hand, there is a growing range of publications, websites and forums that are devoted to leftist analysis and critiques of the "reform" policies. In some cases, these are explicitly "Maoist." More broadly, there are many expressions of a "new" left, which like its Western counterpart, mixes Marxist concepts with sociological and social democratic influences. Among young intellectuals, especially, there is a questioning approach to the widely accepted negative interpretations of the Mao era put forward after his death. But even among "old" leftists, many of whom earlier bought in at least partially to the "reform" policies under Deng Xiaoping, there is a new willingness to criticize the direction of the party and state, and to do so more openly than they had been prepared to do for many years. These changing attitudes have a broad popular base as well, such as the four million or so Chinese—ranging "from backpacking college students to busloads of middle-aged workers on company excursions"—who each year visit Yan'an, the remote base in the Northwest where the Long March ended, and from which Mao led the guerrilla struggle against the Japanese and launched the final showdown with Chiang Kai-shek and the Nationalists. It was there that the goals of the Communists were expanded and perfected, and to it many thousands of both members of the working classes and intellectuals found their way to join the revolutionary struggle under the leadership of Mao. Despite, or perhaps because of its remoteness, this city has remained a symbol of the spirit of sacrifice and closeness to the people that marked the revolution, standing in such contrast to the luxury, corruption and exploitation of the workers and peasants today—despite the efforts of those such as Chang and Halliday, and of some domestic Chinese critics, to debunk its legacy (New York Times, 7/1/05, A4).

Any renewed interest in the early revolutionary period and the "spirit of Yan'an" would be enough alone to worry those who oppose any hint of the revival of "Maoism." But the turn to the left of many young intellectuals, in particular, takes a practical form as well, and one of potentially great significance for the working class struggle, that is even more threatening to those who fear a revival of the alliances of the Mao era. Beginning around five years ago, small Marxist study groups began to emerge on a few of the more elite university campuses. Originally quite isolated and devoted to reading the classical texts of Marx, Engels, Lenin, and especially Mao, these early efforts have blossomed into a much more widespread network of leftist campus organizations today. From a growing number of universities, students are now travelling to cities like Zhengzhou to meet with workers, study and report on their conditions, and offer both legal and material support to their struggles. A similar student organization, the Sons [sic] of the Peasants, is sending student delegations to the rural areas. Though still small, and barely a blip on the general university scene, where most students are devoted only to their studies and careers, these leftist campus groups are nevertheless a dramatic new development in China. Through this movement, hundreds of college students on the left, and those with broad progressive politics, are beginning to gain practical experience of the conditions and struggles of the working classes, and even joining them in opposing the current policies of the state and party authorities—a linkage that has not occurred since the Cultural Revolution.

While still largely marginalized, and subject to harassment by the government—some of those trying to go to Zhengzhou were even denied permission to get off at the railroad station there—these student organizations are rapidly breaking down the great gap that had opened up between intellectuals, and workers and peasants, under the Deng "reforms," when professional elitism and a narrow focus on academic achievement were once again the basis of official educational policy. Attacks on Mao, such as the new one by Chang and Halliday, must therefore be viewed in the context of attempts to head off the growing alliance of the left and the working classes. The younger generation, in particular, must be "inoculated" against the "Maoist" threat. While the book, and even issues of magazines with reviews of it, have already been banned in mainland China, one can safely assume that underground and internet copies will soon be circulating there—since editions are planned for both Hong Kong and Taiwan—and that its major claims will become known at least to a relatively broad range of those who care to track it down.

Mao; The Unknown Story must thus be understood as one entry in the battle for the "hearts and minds" of the Chinese people as they face a critical turning point, whether to plunge completely over the cliff of capitalist restoration and corporate "globalization," or to turn back from the precipice and begin to rebuild a society in which socialism and the working classes have a meaningful role in determining the direction of official policy. In this sense, the Chang and Halliday book is a weapon in the class struggle that has once again begun to emerge in China with gathering force. Its treatment of the conflicts of classes in the revolution makes this clear. In its opening paragraphs, the book states that, "High positions were open to all through education" in traditional Mandarin society, and that those from "any background" could thereby gain wealth and power—a literal truth that blandly disguises and casually dismisses the oppression of the peasantry, and the necessity of revolutionary struggle to end it (4-5). The peasant uprising of the 1920s, in turn, is dismissed as little more than thuggery and banditry, while Mao is portrayed as joining and using it only to advance his own career (41-42). The release of Mao; The Unknown Story is thus part of the strategic moves by those who oppose the new potential for revolution that is developing not only among the Chinese working classes, but within the ranks of the intellectuals, who are turning toward the left and beginning to find ways to reunite with those from whom, since the Cultural Revolution, they were alienated. It is against such a potential for ever higher levels of organized struggle, that the government has issued a renewed warning, "a strongly worded recent editorial, published in People's Daily, the Communist Party's mouthpiece, under the headline 'Maintain Stability to Speed Development.' The commentary warned citizens to obey the law, saying that threats to social order would not be tolerated." (New York Times, 8/24/05, A4). Soon after this statement, an even more stringent crackdown on websites and other forms of electronic exchange was begun.

But it is not only in the context of China alone that Mao; The Unknown Story has significance. For the same forces that are compelling the Chinese people to move in new directions are having a similar effect on the working and "educated" classes worldwide. From this standpoint, it is critical to remember the role that Mao played historically in the global struggles against imperialism and capitalist exploitation. He, like Ho Chi Minh and later Fidel Castro, was a preeminent representative of the unification of national liberation and socialist revolution. It was against this combination, more than any other, that the "Cold War"—which in reality was an almost continuous series of "hot wars"—was conducted. From the U.S. protective umbrella thrown over Taiwan to which the defeated Nationalists escaped after the triumph of the Chinese revolution, through Korea, the Bay of Pigs, Vietnam and numerous "contra" wars in Latin America and Africa, the West struggled to contain and "roll back" Communism by breaking apart the unity of anti-imperialism and socialism most evident in certain Third World revolutions. With the collapse of the Soviet Bloc and the turn of China once again toward capitalism, the forces of U.S. imperialism and their intellectual hangers-on thought that they had once and for all driven a stake through the heart of the threat that leftists posed to their global rule, and that, in the words of Francis Fukuyama, "the end of history as such; that is, the end point of mankind's ideological evolution" had finally and permanently arrived.

But the left refuses to stay in its grave. As the Observer/UK in London noted recently, in response to a two page spread in the right-wing Daily Mail which vilified a "penniless asylum seeker" who "has been dead since 1883," "'Marx the Monster' was the Mail's furious reaction to the news that thousands of Radio 4 listeners had chosen Karl Marx as their favorite thinker. 'His genocidal disciples include Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot – and even Mugabe. So why has Karl Marx just been voted the greatest philosopher ever?'" (6/17/05) "Monster," it seems, is the new favorite term du jour applied to both Marx and Mao, but those who use it are left unable to explain why millions worldwide refuse to abandon them. The answer, as the Observer analyzed, is that capitalism itself continues to provide the left with the fuel for its own revival. The contradictions of the global capitalist system, seen in China today as vividly as anywhere, continually drive not only the working classes, but the intellectuals, back toward leftist interpretations of the world, because these alone can explain what is happening in the lives of the people, and offer the possibility not just of minor adjustments, but the overthrowing, of the system that oppresses them. Marx and his "disciples," including Mao, must therefore once more be totally discredited, and declared to be "Monsters," in order to forestall a global revival of the left and a turn once again by workers and peasants toward the goals of revolutionary socialism. Whether for Fleet Street, or Chang and Halliday, the need is the same, to rally the forces of reaction against the reviving worldwide leftist challenge.

But as in the Chinese case, the threat here is not just ideological. Across the Third World in particular, but even in the core countries of the empire, tens of millions are now challenging capitalist "globalization" on a daily basis. The turn of Latin America to the left, the resistance of the most oppressed and marginalized indigenous members of global society to economic and environmental depredations, the growing struggles of Asian workers and peasants against the capitalist multinationals and the vast polarization of their societies, the demands from Africa for debt relief and the right to low-cost drugs for AIDS, and the massive demonstrations which greet the leaders of empire wherever they gather, most recently in Scotland for the G-8 summit—all are signs of this struggle. The present movement represents an unprecedented upsurge of popular organization against the corporate ravaging, environmental devastation, and economic and social polarizing that is the inevitable accompaniment of the unleashing of an unrestrained capitalism.

But as was true during the Cold War, the "anti-globalization" aspects of the struggle—that is, resistance to the U.S. dominated empire and expanding corporate control—and its anti-capitalist, and especially pro-socialist, elements are hard to bring together. In formations such as the World Social Forum, which has been at the forefront of the "global justice" movement, and especially among its participants and followers in the United States, there are strong strains of resistance to the legacy of both the socialist revolutions and to leftist ideology in general. There is little meeting ground between many of its activists, and revolutionaries such as the Nepalese or Peruvian "Maoists," or the Marxist guerrilla movements in Colombia or the Philippines, or even, for some, the Zapatistas from Chiapas, who hardly fit the more traditional "model" of such struggles. Even the millions of working class protesters in China have received little attention from the "anti-globalization" forces, not only because of their limited ability to take part in gatherings such as the WSF, but perhaps because they too are considered tainted by socialist revolution and "Maoism." (see John Gulick, "Insurgent Chinese Workers and Peasants," in Confronting Capitalism; Dispatches from a Global Movement, Eddie Yuen, Daniel Burton-Rose, and George Katsiaficas, ed., Soft Skull Press, Brooklyn, NY, 2004) Many in the global justice movement, of course, do identify themselves as socialists, though of widely different varieties—and, for example, eagerly support the "Bolivarian Socialism" of President Hugo Chavez in Venezuela, where the 2006 WSF will be held.

But just as in the era of anti-colonialism, only in certain cases do rebellion against the imperial system and socialist revolution come together in a sustained fashion, and this lack of unity remains one of the greatest weaknesses again today. As in China, therefore, it is necessary for the imperialists and their ideological supporters to do everything in their power to prevent any deepening ties of the working classes and the revolutionary forces of the left, of the global justice movement and the struggle for socialism. The existing divisions, which already weaken the forces that oppose both the U.S.-dominated empire and the capitalist system, must therefore be further exacerbated. The book by Chang and Halliday must be seen as part of this global battle, a worldwide right wing reaction, to head off as much as possible the unification that Mao represented of both anti-imperialism and socialist revolution, which threatens to rise again, even stronger.

Of course, the point here is not that Mao; The Unknown Story or the reviewers of this work explicitly address all of these various aspects of the current global struggle in their attack on him, but rather that they are one part of the general anti-left "atmosphere" of the present time, and that they share the ideology expressed in other ways by those with similarly reactionary views. This situating of the book as part of a worldwide class conflict and ideological battle, also points to the direction that will have to be taken in countering its claims. Each of the specific "charges" that the authors bring against Mao will have to be confronted, and despite assertions of those like Philip Hensher, they will not be "unanswerable." Their refutation will rest first and foremost on those who knew and worked with Mao directly, as previously occurred in the case of Li Zhisui, when former comrades in the party and state denounced his claims and defended both the personal character and the revolutionary accomplishments of the Chinese leader. But since Chang and Halliday cite many such earlier associates of Mao themselves, this will mean helping to mobilize those who hold opposing views to come forward with their own counter version of key events and remembrances of his work and life. In this, historians and "China scholars" will also no doubt join in, bringing a more nuanced and balanced review of the record of the Mao era. At the same time, the methodology of Chang and Halliday, and in particular their loose approach to documentation, highly selective and biased use and interpretation of historical events, and contradictions with their own earlier works will have to be addressed. Such questions need not be raised only by the left. They have already been partly conceded even by some of the most virulent early reviewers, and exposed by those who take a more objective and critical approach. "China scholars across the world are questioning the veracity of historical accounts" in the book, as well "as factual errors and dubious use of sources – which even favourable reviewers such as Princeton's Perry Link (an editor of the Tiananmen Papers) have felt compelled to criticize." ("Throwing the book at Mao," www.theage.com.au, 10/6/05) Similarly, Kristof, noting the range of estimates put forward for the number of deaths in the Great Leap Forward, accuses the authors of "Simply plucking a high-end estimate out of an article and embracing it as the one true estimate . . . ." (11) It is not just that Chang and Halliday pick and choose their evidence to prove their case, however, or that others argue for even lower estimates than those cited in the book and reviews (see, inter alia, Utsa Patnaik, "The Republic of Hunger," Public Lecture, New Delhi, 4/1/04). For the same campaigns in which many died, primarily during the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, also saw the introduction of health care and other social programs for the working classes, and especially the peasants, that saved and extended the lives of tens of millions, and raised China to unparalleled levels of life expectancy and literacy compared with such similarly poor Asian countries as India and Indonesia. Thus both the gains and the costs that the Chinese experienced during the revolution were closely interwoven, but Mao; The Unknown Story totally ignores any positive accomplishments. Still, a more thorough confrontation with and refutation of the claims of Chang and Halliday will have to await a broader distribution of their book, and especially access to it in China. Such a detailed rebuttal will take time, and require a very sustained and determined struggle.

But one issue can be addressed early on by those who have no direct experience of Mao, or special expertise in the details of the historical record of his leadership. This is the view, summarized by Simon Sebag Montefiore in his review, that the "authors . . . believe that Mao was never a Marxist, simply an opportunistic egomaniac." Kakutani in his New York Times review similarly notes that "the authors declare that Mao lacked a 'heartfelt commitment' to Marxism." Those familiar with the history of leftist theory and analysis know that there has long been debate and disagreement over the nature of the Marxism practiced by Mao, in particular regarding such questions as his dependence on a "peasant army" as the main force of the revolution in China, which some claim breaks with "classical" Marxism-Leninism, or his conflicts with the Soviet Union on the issue of revisionism and his opening to the West. To this day, the ranks of leftists across the world are frequently divided by whether they follow the interpretations of Marx that were advocated by Mao or competing tendencies. It is problematic whether Chang and Halliday are competent to enter into the finer points of this discussion from a Marxist standpoint, but regardless, any assertion such as that attributed to them by Montefiore is ridiculous and refuted by the writings of Mao himself. From his first works, such as "Analysis of the Classes in Chinese Society" and "Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan"—building on the work of Engels and Lenin in particular—through which the revolutionary uprising in the rural areas was given theoretical and practical guidance, and on which the land reform movement was later based, through his outlining of the class alliance needed to defeat the Japanese, to his addresses to the "Yenan Forum on Art and Culture," and his last writings on the continuation of the class struggle on the ideological plane in the era of the transition to socialism, Mao not only was thoroughly based in the fundamentals of Marxism, but made profound and lasting contributions to the expansion of its canon. His theoretical essays, such as "On Contradiction," brought to an entire generation of the left, not only in China, but worldwide, a deeper understanding and extension of Marxist dialectics. In the United States, these and similar works had a formative influence on such diverse groups as the Black Panthers, Redstockings—part of the most radical wing of the Womens' Liberation Movement—and various alternative academic and professional bodies. Above all, Mao made basic concepts of Marx accessible to hundreds of millions of workers and peasants.

The attempt by Chang and Halliday to dismiss Mao as "never a Marxist" says more about their own approach, therefore, than about the Chinese leader himself. Their interpretation of his report on the Hunan peasant uprising, for example, reduces it to nothing but a supposed discovery by Mao of his love of violence (41-42). A similar treatment allows them to avoid any hint, much less an indepth analysis, of the impact of his writings on the class struggle and policy conflicts not only in China, but around the world. That a virulent animus pervades their work and biases all of their interpretations has already been noted by some of the more middle of the road and "balanced" reviewers of their book, such as James Heartfield who, while by no means rejecting every aspect of its conclusions, made a well researched effort to expose the distortions contained in their account. His review addresses gaps in their theses, facts and methods, and in particular notes that they "struggle to explain Mao's victory in their Unknown Story, because their hostility to their subject forbids any credit whatsoever" (James Heartfield, "Mao; The end of the affair," www.spiked-online.com, 7/4/05). Kakutani criticizes the lack of reference to his "mature writings that might shed light on his politics or values," and the absence of historical context, calling the work "tendentious and one-dimensional." So too, Kristof complains that in the book, "Mao comes across as such a villain that he never really becomes three-dimensional," and that he is "presented as such a bumbling psychopath that it's hard to comprehend how he bested all his rivals to lead China and emerge as one of the most worshipped figures in history" (11). Here lies the fundamental flaw in the attempted "trashing" of Mao by those like Chang and Halliday and others of their ilk. For what such a dismissive approach cannot account for is how the largest revolutionary struggle in world history, stretching over more than half a century and involving between a fifth and a quarter of all humanity, overturning the millennial class structure of the Chinese empire, defeating internal enemies and external imperialism, and transforming the lives of hundreds of millions of workers and peasants in the most profound ways, can have been accomplished with the kind of leader that they picture Mao to have been.

Such an attempt to reduce history to primarily the role of "great personages"—and in this case a supposedly monstrously evil one—denigrates both the struggle and wisdom of the people of China, and in particular its working classes, who followed him through thick and thin, victories and defeats, vast accomplishments and terrible losses. It also ignores the complexity of any social transformation, especially one on the scale of the Chinese revolution, and of those who lead it. Mao, like all the great revolutionaries, was a product of both his time and culture, who despite his profound radicalism, was nevertheless bound by the limits of the society of China that he inherited, and inevitably, as both a human being and as a leader, showed weaknesses as well as strengths. His record as the primary guide of the decades-long Chinese revolutionary struggle, must be and is constantly being reviewed, within the context of not only China itself, but the powerful global forces shaping his times. Both the great victories of the revolution and their extremely high cost are part of this necessary review. Any efforts to dehumanize Mao into a one dimensional "monster," however, such as he is portrayed in the book by Chang and Halliday, result not in a better historical understanding, but become instead an empty exercise in warped political propaganda.

The emergence of a campaign to refute Mao; The Unknown Story has already begun, in a few more balanced and critical reviews of the book and on leftist websites and email lists. In the last analysis, however, it must be recognized that the intellectuals and journalists on the left, and even some of those more in the political mainstream, who reject all or part of the thesis of Chang and Halliday, are in a weak position acting by themselves in refuting its distortions. For they can never match the power of the print and electronic media of the right wing corporate monopolies, largescale book publishers, and quasi-governmental global radio networks such as the BBC, which reach hundreds of millions on a daily basis. Against such opponents, the resources of the left will always be grossly inadequate. But the battle is not and should not be confined to the field chosen by the reactionaries, who believe that they can win the day by promoting such attacks. For in the end, the struggle will not be determined primarily by whether those who read such books accept or reject their conclusions. As Mao himself made clear, "The people, and the people alone, are the motive force in the making of world history," ("On Coalition Government," May 24, 1945). It only needs to be added, that they, and especially the working classes, in their hundreds of millions, are also its ultimate arbiters. In the end, it is the Chinese people as a whole, and above all the workers and peasants—along with billions of their peers around the globe—who will render the lasting historical judgment as to whether Mao helped to make their lives better or worse. Those who have spent even a small amount of time talking with members of the working classes of China know that the view of him and of the socialist revolution that he led, while today by no means unquestioning or uncritical, still remains deeply appreciative and approving, and he continues to be seen by many as their representative. This is especially so, when they compare the "Maoist" era with that of the current rulers, who are viewed as corrupt and defending only the interests of the growing ranks of exploiters in the party and state and the rapidly emerging capitalist class, which is daily driving the workers and peasants to desperation, and the edge of open revolt . As Wu Guoguang, a former government adviser and People's Daily editorialist now teaching in Canada put it, "'the masses are angry basically because of abuse of power by party officials. If the government were clean and efficient, things would be much calmer. But the perception is that the officials don't want to pursue the state's interests, so much as pursue their own interests—both legal and illegal'" (New York Times, 8/24/05, A4).